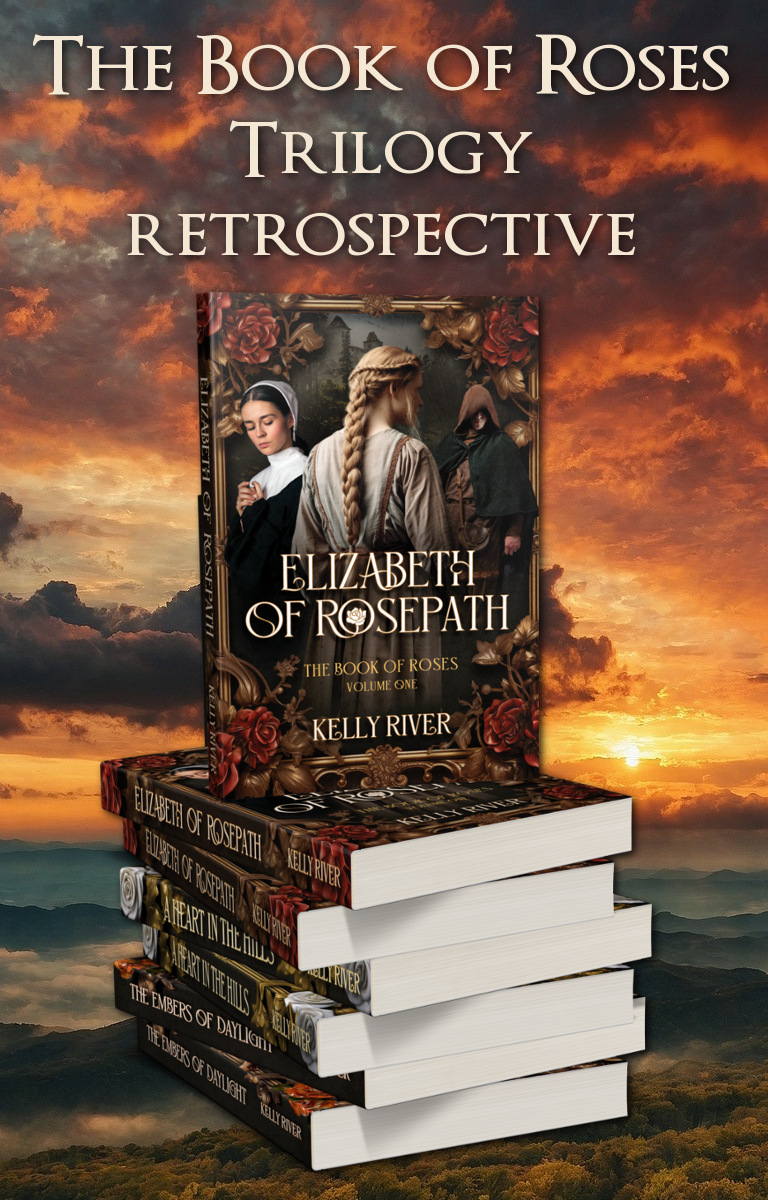

This post contains major spoilers for Elizabeth of Rosepath, A Heart in the Hills, and The Embers of Daylight

For a while now I’ve been mulling the idea of writing a post discussing the Book of Roses trilogy in more depth, something of a retrospective on those first three books and how I approached writing them. But when I thought about how to structure it, I realised that it was mostly a series of disconnected thoughts. I wasn’t really sure how to tie them together into a holistic article, so I decided, you know what, let me just give you a list of some of the most interesting tidbits I thought were worth sharing. If this was a clickbait article, it would be titled “top ten things you NEVER knew about The Book of Roses” (though there will not be ten and they’re in no particular order).

So without further ado, let’s get to it!

The trilogy was originally supposed to be one novel, but I vastly underestimated how long it would be. This, I later realised, was mainly down to having four main characters. When I first started writing, Elizabeth was supposed to be the only protagonist. I expected most if not all of the story to be told from her perspective and for the scope to be relatively narrow as a result. But as more characters started taking on lives of their own, I realised I needed time to do them all justice. Edward, Kaylein, and Isaac all had their own narrative arcs to go through, and each one could have been a novel in its own right.

Leading on from the previous point, Kaylein wasn’t intended to be a major character. She existed in my mind even before I’d started making any notes, but I didn’t expect her to be an integral part of the story. She was mostly there as a source of conflict Elizabeth would have to deal with in the early part of the first novel. I expected them to eventually part ways as Elizabeth’s problems rose to the forefront, but as soon as I started writing Kaylein’s first chapter in the convent, I realised she had her own story to tell. The contrast of parallels between her and Elizabeth always made it fun to switch between writing one character and the other. While Elizabeth’s conflicts tend to be simple, pragmatic, and down-to-earth, Kaylein’s are far more academic and high-minded. While Elizabeth struggles to find a better place to live, Kaylein frets over questions of religious morality. Elizabeth’s ultimate goal is to settle down and live a comfortable life, while Kaylein has aspirations to change the kingdom.

This, to me, was what made both characters so interesting to write. I think Elizabeth resonates on a universal emotional level while Kaylein is more nuanced and conflicted. One of my favourite scenes between them is when they argue over the morality of Elizabeth running Elspeth’s brothel. I felt like both their personalities came out very strongly in that moment, demonstrating Elizabeth’s no-nonsense “this is what’s right in the here and now” attitude coming into conflict with Kaylein’s large-scale ethical and sociological objections. I was careful not to try and paint either of them as being clearly in the right or wrong (though I expect most readers will lean more towards one than the other), as I think that scene underlines some of the greatest strengths and flaws in both their characters.

All of that to say, I’m very glad Kaylein ended up being more than just a side character! If you asked me to pick my favourite protagonist from the trilogy, it might just be her.

Isaac was a character I originally planned to feature in a future novel. At one point, I had it in mind to write three books titled “Elizabeth of Rosepath,” “Kaylein of Kinedwyn,” and “Isaac of Nowhere,” mostly just because I thought those titles sounded neat. I didn’t know much about who Isaac was at that point, only that he’d be a romantic soul full of wanderlust who struggled to put down roots. It was the decision to make him Count Francis’s son that really crystallised his character and made me want to pull him in as a protagonist in the first book. Having a character with blood ties to Francis opened up a brand new angle of the story for me to work with, ultimately paving the way for the dramatic events at the end of Heart in the Hills.

It should come as no surprise that Edward was the most difficult character to write. Not from a technical perspective–he’s really quite a simple man when you boil it down–just from the visceral unpleasantness of some of his scenes. I wanted him to be loathsome, but realistically so. I knew I couldn’t sustain a moustache-twirling villain for three whole novels (there’s only so many times you can read about someone kicking puppies before your eyes start to glaze over), so I tried to find the humanity in him and turn that into a source of friction. His greatest weakness is that he’s emotionally immature. When I was writing him, I tried to put myself in the perspective of a child reacting with anger and outrage to adversarial situations, a response that most people learn to temper as they grow up. Edward never learned how to temper it, but he is socially aware enough to understand, deep down, that his behaviour is unacceptable. So instead of confronting his immaturity, he finds ways to justify it using the structures he believes in. When he’s cruel to someone, it’s because they deserve it for violating whatever principle Edward decides to use as a shield. He convinces himself that titles, laws, fealty, and duty are all ironclad concepts with intrinsic moral value. If he can explain away his actions within their context, he can do no wrong.

In my experience, this is the way most deliberate evil ends up happening in the real world; actions stemming from a place of ignorance or immaturity masquerade as virtue because the perpetrator is unwilling (or unable) to turn around and take an honest look at themselves.

Edward’s ending was inspired by the fate of Inspector Javert from Les Misérables. Spoilers ahead if you’ve never seen/read Les Mis. I think I was in my teens when I came across the ending of Javert’s story for the first time, and I remember thinking, “Wow, that’s so much more satisfying than when the villain just gets killed off at the end!”

For those who aren’t familiar with Les Misérables, Javert is a police inspector who spends much of the story fanatically hunting Jean Valjean, a man he believes to be evil because he is a criminal. When, at the end of the story, Javert’s worldview is shattered by the realisation that Valjean is a good man and his hunt has been misguided, he suffers a breakdown and commits suicide. Javert is one of those rare examples of a villain who destroys himself when he is forced to confront the flaws in his character. This, to me, is the most satisfying comeuppance an antagonist can get, as it completely unravels everything you grew to hate about them rather than simply cutting it off with an abrupt end.

I wanted to take this one step further with Edward and force him to live with the consequences of his actions. I have a feeling that some people might have been disappointed that Edward didn’t die at the end of The Embers of Daylight, but to me, having to live through his ego death and keep on going is far more satisfying. Not only does he get his comeuppance for everything he’s done, but there’s a hint that maybe, just maybe, he might go on to try and atone for it in the future.

One thing I definitely wanted to make clear though is that he never bothers Elizabeth again. Since so much of her hardship in the trilogy stems from the threat of Edward looming over her, I broke one of my own narration rules in Edward’s final chapter to give a little bit of omniscient foreshadowing with the line: The last Edward ever saw of Elizabeth of Rosepath was her straw-coloured hair drifting behind her as she turned away into the crowd.

Even if he’s not dead, we know for a fact that he never troubles her again. It isn’t the physical punishment or the humiliation Edward suffers in his final chapter that ultimately undoes him, it’s the way his denial finally shatters and, just like Javert, he realises he’s been the villain all along.

If I had to rewrite the trilogy, the one major thing I might change is how disconnected Edward is from the rest of the characters in book 2. He doesn’t interact directly with them very often in any of the novels (except perhaps Isaac in book 3), but I thought the ripples of his actions were felt much more strongly in books 1 and 3. There’s a lot of direct cause and effect in those novels, while in Heart in the Hills he’s mostly absent doing his own thing. His perspective is still important to contextualise the events of the war and set things up for book 3, and I find his personal story engaging in its own right, but it irks me that he doesn’t cause more problems for Elizabeth and the others. One of my pet peeves in storytelling is disconnected narrative threads that take a long time to intersect. I like to overlap things as often as possible, or at least draw connections between them. One of the reasons I had to introduce the character of Rufus and create conflicts with the Kinedwyn village council is because I didn’t have Edward around to stir up trouble.

Heart in the Hills would have been a very different book if Edward was ever-present, and while I do enjoy the atmosphere of low-key village life his absence makes room for, I feel like I could’ve come up with a way of integrating his side of the plot more closely.

Ironically, given what I just said in the previous paragraph, if you made me pick a favourite book of the trilogy, it would probably be Heart in the Hills. I really enjoyed the slower, cosier pace of that novel and the cast of villagers in Kinedwyn. It’s the book where all the characters come into their own and start to self-actualise, and the dramatic highs are some of my favourites in the trilogy. Perhaps it’s just editing trauma, but Elizabeth of Rosepath always felt a little messier to me. That book is very much about setting the characters up before they get to embark on their arcs, while Embers of Daylight is a more sombre novel, especially at the beginning.

I’m not an author who generally likes to ascribe themes to my work–in my mind, that’s something for you the readers to decide on–but looking back on the trilogy, I do think the pervasive tone of The Book of Roses is one of hope. Despite how dark the series sometimes gets, I’ve always had a strong affinity for stories that involve people falling down so they can get back up. When the characters lose everything, they always find a way to keep going, even when it means turning away from the path they were on before. I don’t see my characters as having indomitable spirits, but rather adaptive ones. While I’m a huge fan of whimsy and romanticism in storytelling, I also like to ground it in something real. Many of the strongest people I’ve known are those who can roll with life’s punches, not those who grit their teeth and try to power through without flinching. None of us are superheroes, and the ability to evolve and change as the world changes around us is what’s allowed us to thrive.

In the final chapter of the trilogy, Elizabeth delivers the line: “Kaylein says in her book that life is all petals and thorns. You can’t pretend it’s all one or the other. I think the sharper the thorns are, the brighter they make the petals look.”

I wouldn’t go so far as to call that a declaration of theme, but it’s definitely a nod to how I approached the storytelling. It’s all about sharp thorns and bright petals.

That’s why I called it The Book of Roses, by the way. I didn’t even know Kaylein was going to write a book of the same name until well into the third novel.